A Dark Cycle

When history repeats itself

I recently took a trip to western Kansas to explore a part of the state I’ve never visited. I live on the east side, near Kansas City.

We drove along a route called the Western Vista’s Byway. Geologically, it may qualify as the most interesting part of the state. The history of this area is also rich, and instructive.

One of the stops along the byway near Lake Scott is called Punished Woman’s Fork, also referred to as Battle Canyon. I suspect this identification depends on whose point of view you consider. The Cheyenne people originally named it. T hey were familiar with the location, which was why they chose it as a place to make a stand against a more numerous, well-armed foe.

According to tourist information, this is the site of the last battle between Plains Indians and the U.S. Army in Kansas, which took place in the fall of 1878. Below is one of the pictures I took from a high ridge overlooking the canyon, which is deeper than it appears in this photograph.

The information posted points out the rifle pits the Cheyenne strategically positioned to “ambush” the soldiers. Was an ambush their intention? It really appears more defensive than offensive. The women, children and elderly people were huddled in a cave at the end of the canyon (see below).

One the signs originally stated soldiers were engaged by the Cheyenne warriors. Someone had marked out a few key words so that the sign now reads soldiers engaged the Cheyenne warriors. That small change shifts the perspective of the reader and how the event might be interpreted.

The Long Way Home

Let me take a step back and set the scene. After protracted conflicts with the U.S. Army (which cost the Plains tribes a majority of their young men). the Northern Cheyenne finally signed a treaty. They agreed to move to a reservation some seven hundred miles south in a territory that would eventually become Oklahoma.

They were told their new home had plenty of wild game and they would be able to hunt and feed their families. In truth, it was land the government deemed worthless enough to give away, and the game had all been chased off or slaughtered.

Impoverished, hungry and sick, the Cheyenne informed the Indian agent they wanted to go home. The treaty clearly stated they could. But they were told they couldn’t.

Determined, the leaders stole away in the dead of night with a handful of warriors and three hundred women, children and old folks. The journey took them directly through old hunting grounds, now occupied by white settlers.

The army went after them.

I won’t go into detail about the chase or the battle, other than to say that the Cheyenne were well-prepared for an assault, but the pursuing soldiers, having recent memory of Custer’s blunder, figured out the plan and were able to avoid another embarrassing and disastrous encounter.

After a pitched battle, the Northern Cheyenne slipped off during the night. One Cheyenne warrior had been killed, and the army commander, Col. William H. Lewis, was mortally wounded.

The aftermath of this battle is as tragic as it’s cause. Several accounts say Cheyenne raiders stole livestock and attacked white settlers. But that doesn’t tell the whole story. Stragglers who couldn’t keep up, mostly women and children, the wounded, and the elderly, were caught along the way and executed by soldiers or civilians. One small group was arrested and tried for murder but ultimately released for lack of evidence.

Eventually, those who survived the journey were reunited in the place they had called home. The Northern Cheyenne were allowed to remain on a much smaller parcel of land with the promise they would stay put and not roam their former hunting grounds. Their homeland no longer belonged to them.

Fleeing From Persecution

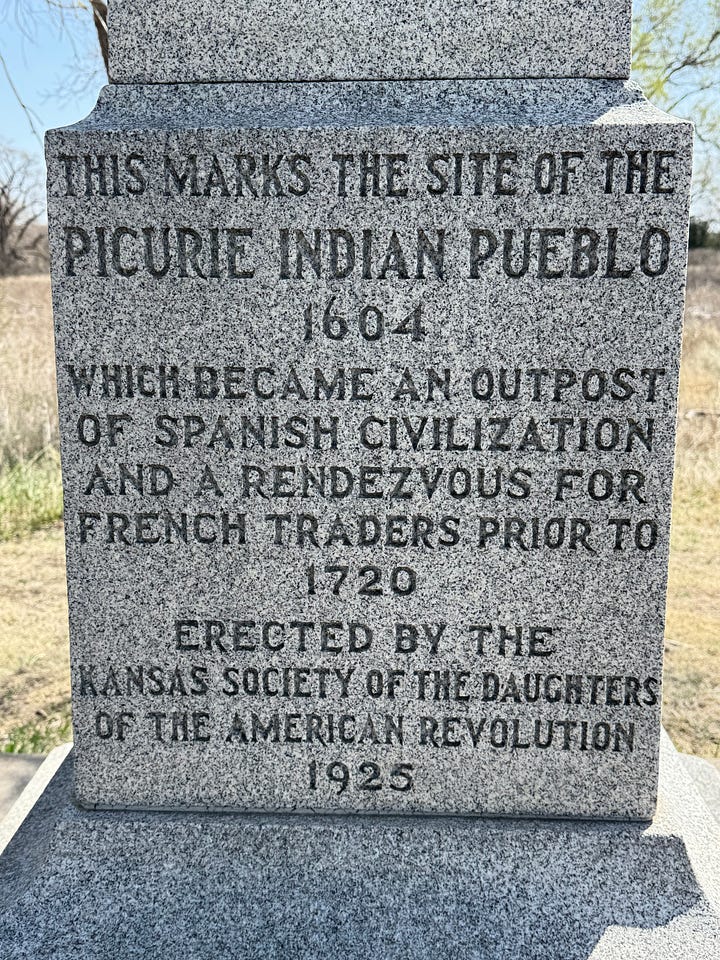

An earlier story about immigrants is just down the road at El Quartelejo (also spelled El Cuartelejo), on the grounds of historic Lake Scott State Park.

This site is billed as the ruins of the northernmost pueblo in the United States. The ancestral home of the Picuris Pueblo is in New Mexico, near Taos. It was once one of the largest Tiwa pueblos, but today it is the smallest with about 1,800 inhabitants.

Archeologists think the remains of a small seven-room pueblo structure in western Kansas is the location referred to in 17th century Spanish reports. The village was originally inhabited by the Cuartelejo Apache. Picuris refugees fled there to escape Spanish rule. They met up with their friends, the Apaches, and built a small structure in the Puebloan style. See below.

The Spanish sent soldiers after the refugees and rounded them up and took them back. Frankly, I’m not sure why. Possibly, they needed laborers. Or they didn’t want the Picuris stirring up trouble or giving the Apaches any ideas. The information I read doesn’t say.

In the end, the Spanish and French fought over land that wasn’t theirs to begin with, and then sold it or lost it to the Americans, who had no rights to the land either.

Let’s fast-forward to our situation today in the land of the free.

A nation started and built by immigrants is now expelling immigrants. Without due process, which is a right extended to all persons on our soil, according to the U.S. Constitution.

From the Fourteenth Amendment: No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The Supreme Court expanded on the Due Process Clause to include (1) “procedural due process;” (2) the individual rights listed in the Bill of Rights, “incorporated” against the states; and (3) “substantive due process.” In other words, Due Process is a long-standing and well-developed right in the United States of America. After all, if a government can snatch people off the street and expel or imprison them without giving them a chance to defend their innocence, the people have no rights. Period.

The Trump Administration’s mad rush to expel immigrants isn’t limited to adults. ICE agents are demanding that schools give them access to undocumented children. Sadly, this isn’t the first time our government has targeted kids either.

During the late nineteenth century, authorities removed Native American children from their families and tribes and sent them to boarding schools to force assimilation and eradicate their cultures.

I’ve highlighted just a few examples from our historical archives. The ones that haven’t been erased.

Recently, Kristi Noem, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and a cadre of smiling Republican Congressmen posed in front of caged men at El Salvadore’s notorious lock-up where our government is illegally sending immigrants. These images called to mind the grainy newspaper photos of white men, women and children having their picture made at a public lynchings of black men and women in the 1920s. I’ll spare you the visuals. The point is, dehumanizing other people leads to the worst offenses against humanity. Not only does this kind of behavior violate our laws, it corrodes our souls.

Another story I encountered on my recent travels is one that gives me hope.

In the Fick Museum in Oakley there is a tribute to a woman who lived in Colby, Kansas during the early years of the 20th century. Zelma Hurst was black. Most of the students in the small rural schools she attended were white. This, however, isn’t what made her famous.

Zelma grew up, married and moved to Topeka, where she was forced to drive her children across town to attend a segregated school. She became one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit—Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education. The case made it all the way to the Supreme Court and led to a decision that ended nationwide segregation in our schools. That’s what made her famous.

In a newspaper article published years later, Zelma said she hadn’t sought out attention, but gladly became a plaintiff in the case because she’d experienced what it was like to attend integrated schools. “We got to know one another and learned how to get along.” She wanted that experience for other children.

Zelma Hurst Henderson knew the secret. When people get to know each other, when they listen to each other’s stories, when they meet each other’s families and nurture an open mind and a generous heart, they can learn how to get along and can stop repeating the same terrible mistakes based on ignorance and false narratives.

This is the future I want for my children, too.

Currently, there is a government-sponsored effort underway to literally whitewash our history and remove stories about people like Zelma. This won’t make the past or the people they are trying to erase disappear. We are repeating the dark cycle, fueled by the same, tired falsehoods of white supermacy and religious intolerance. Ultimately, this becomes a downward spiral into our destruction. Resisting these forces will require the same determination and sense of justice that propelled the Civil Rights movement. Resistence is hard. Losing our country will be harder.

Links and Resources

Northern Cheyenne history: https://mhs.mt.gov/education/IEFA/NorthernCheyenneTimeline.pdf

A nice overview on the historical background of Punished Woman’s Fork: https://roxieontheroad.com/the-battle-of-punished-womans-fork/

Picuris Pueblo information from New Mexico tourism: https://www.newmexico.org/native-culture/native-communities/picuris-pueblo/

Scott County, El Cuartelejo history:

https://www.kansashistory.gov/kansapedia/el-cuartelejo-scott-county/12026

A historical sketch of Zelma Hurst Henderson:

Fascinating post. I’m overdue to make the same trip west, including a stop in Hays to visit the Fort Fletcher museum. Apparently, my great great grandfather was a colonel in charge there. I think he might’ve been responsible for some of the actions you described here. Anyway, I need to learn more.